Ronald Josiah Taylor (1934 – 2012)

© 2012 by Douglas David Seifert, World Editor, DIVE Magazine and Board member, Shark Savers

Ron Taylor, Australian icon of ocean exploration, scuba diving pioneer and innovator, visionary underwater filmmaker and marine conservationist, left this world behind early Sunday morning as he made the ultimate plunge into the eternal sea of night.

Ron Taylor, Australian icon of ocean exploration, scuba diving pioneer and innovator, visionary underwater filmmaker and marine conservationist, left this world behind early Sunday morning as he made the ultimate plunge into the eternal sea of night.

In 2003, the Order of Australia was awarded to Ron Taylor “For service to conservation and the environment through marine cinematography and photography, by raising awareness of endangered and potentially extinct marine species, and by contributing to the declaration of species and habitat protection.”

Born in 1934, appropriately under the star sign of Pisces the fish, Ron first submerged into the seas off Botany Bay, Sydney in 1951, when he found a mask someone had lost at the Brighton Le Sands meshed baths. “The underwater world became clear and I was hooked,” as he confided.

At first, he was a breath-hold skin diver, eventually becoming proficient as an underwater hunter with a speargun from 1953 forward. At this time, he was employed as a photo engraver in Castlereagh Street, Sydney.

In 1955, Ron built his first underwater breathing apparatus from parts purchased from a World War Two surplus shop, based upon an oxygen demand regulator used in high flying aircraft, along with flexible gas mask twin hoses; a fire extinguisher bottle was used for the air supply tank and compressed air obtained from a local engineering firm. The creation worked but was limited due to the small volume of air it could carry for the very short duration scuba dives. Eventually, manufactured scuba equipment made its way to Australian shores and Ron was able to spend greater amounts of time exploring the underwater world.

In 1956, he became a member of the St. George Sea Dragons Spearfishing Club in Sydney and ultimately won four consecutive Australian National spearfishing championships between 1962 and 1965. He reached the apex of the sport in 1965 when he represented Australia at the World Spearfishing Competition held in Tahiti, French Polynesia, and took the top honor as the World Spearfishing Champion.

Over time, competitive spearfishing began to lose its appeal to Ron, because in addition to joining the St. George Spearfishing Club in 1956, he had also discovered the satisfactions of hunting sea life for the camera. He was lent a 16mm Bell and Howell movie camera and built his own underwater housing for it from Perspex, a harbinger of the dozens of Taylor-made, custom-built underwater housings he would construct for all of his cameras over the next fifty years. The film length for that original camera was 50 feet, which would run for 80 seconds in total, but due to limitations of the spring winding mechanism, the maximum the camera would run was 25 seconds before shutting down. Ron learned early on to be very selective in his choice of subject and in camera technique. It was at this time, Ron also became aware that non-divers – also known as the rest of the world – were keenly interested in sharks and he began to specialize in photographing sharks for the camera.

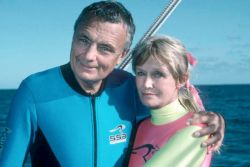

In 1960, Ron bought his own Bolex camera, built another housing and began making films for theatrical release. He also attended the Heron Island Dive Festival where a beautiful blonde skin diver named Valerie Heighes caught his eye. She had won the Miss Heron Island competition and he convinced her to model underwater for his camera, the beginning of a collaboration of filmmaker Ron and on-camera personality Valerie that would endure as a tried and true formula for the next fifty-two years.

By 1962, Ron’s first film, Playing With Sharks was released in cinemas by Movietone News.

The film was followed by Shark Hunters, shot in black and white, and sold to Australian and American television, cementing his reputation as a top-notch underwater filmmaker with a penchant for capturing sharks on film. In December of 1963, he and Valerie married and the following month, Ron won his third Australian National Spearfishing Championship at Kangaroo Island, South Australia. His film Skindiving Paradise was commissioned and released by the Queensland Government Tourist Board.

In 1965, Ron Taylor filmed the underwater sequences for Revenge of a Shark Victim, a 16mm documentary for TCN9 television. In the process of filming, Ron became the first man in the world to film a great white shark underwater and the first man to photograph a great white shark underwater without the use of an anti-shark cage. The resulting image, taken from a single still frame of that film, has been seen the world over for nearly forty years as the embodiment of the fearsome great white shark, a triangle of pointed snout, vast, open, outstretched jaws framed with triangular pointed teeth and featureless, jet black eyes. This iconic image was captured a decade before the movie Jaws gave movie-goers and swimmers a second thought. The year also saw the release of Surf Scene a diving and surfing documentary that played on a festival circuit as the newlywed Taylors barnstormed around coastal Queensland and New South Wales, Australia, four walling a town with posters promoting the film’s showings where the collected admissions paid for gasoline and food and film stock as the Taylors tried to make a career out of filmmaking and following their passion for the sea.

At the same time, Australia’s premiere underwater hunter became completely and irrevocably disenchanted with competitive spearfishing and gave up the sport completely, though he remained a highly skilled spearfisherman the rest of his days but took only enough to put upon the table fish enough to feed himself and his wife, with no waste.

In 1969, American department-store heir and filmmaker Peter Gimbel hired the Taylors take part in the production of Blue Water, White Death, a milestone cinema verite documentary that lived up to its subtitle: “The Hunt for the Great White Shark”. Valerie was employed as a safety diver and on-camera talent; Ron as cameraman. On this six month odyssey, the Taylors, working with Gimbel and cinematographer Stanton Waterman travelled around the Indian Ocean on a chartered whale catcher, from Durban, South Africa, and encountered vast schools of oceanic whitetip sharks feeding upon the carcasses of sperm whales killed by the then-active South African whaling industry. They filmed the shark aggregation at night and they filmed it most memorably by leaving the safety of anti-shark cages. The footage remains, to this day, the most dramatic underwater shark footage ever seen. The producer’s hope was a great white shark would appear at the whale carcass but the virually mythological shark remained elusive, so the production moved up the east coast to Mozambique, to the Comoros and to Sri Lanka, having great adventures along the way, providing a lively travelogue, but not meeting their objective. Eventually, after a hiatus, and at Ron Taylor’s suggestion, the production moved to South Australia where they finally found the great white shark. The film broke all box office records for a documentary film and was second grossing film of the year after only Love Story. The film was a lost classic for decades following Gimbel’s death until the original print was found and re-mastered and re-released in theatres and on DVD in 2007.

Following the worldwide success of Blue Water, White Death, in 1970 and 1971, the Taylors embarked upon filming the 39 episode television series Barrier Reef and the following year, their own television documentary series, Taylor’s Inner Space, which consisted of 13 half hour episodes filmed around Australia.

Their work in Blue Water, White Death attracted the attention of Hollywood and in 1974, Ron and Valerie were promptly hired to shoot the live action great white shark sequences for Jaws. Other film work for Hollywood features followed, with Ron in great demand for original shark footage for Orca, Gallipoli, The Last Wave and all the underwater photographic work for The Blue Lagoon, starring Brooke Shields and Chris Atkins, as well as numerous television works such as pieces for National Geographic, Wild, Wild World of Animals TV series, resulting in specials and features such as Sharks, Silent Hunters of the Deep and Operation Shark Bite.

During this time, Ron’s innovations into the world of experimentation with sharks included the development of a revolutionary, stainless steel, chain-mail inspired, anti-shark suit, as featured in the May, 1981 cover story of National Geographic Magazine.

In the 1980’s, Ron Taylor’s productions of The Wreck of the Yongala and The Great Barrier Reef, both educated viewers about Australia’s irreplaceable underwater heritage concerning the Yongala, Australia’s most dynamic wreck dive and the Cod Hole, a sanctuary for the large and charismatic giant grouper called Potato Cod that could (and thanks to the Taylor’s efforts still can be) found only at one specific location on the Great Barrier Reef. These films, in addition to intense lobbying at great personal cost (threats and denouncement by fishermen and politicians) by Ron and Valerie Taylor, led public opinion towards the then-new concept of marine conservation and forced reluctant Queensland politicians to protect Australia’s unique marine heritage.

Ron Taylor’s footage and presentation of marine life in Australian waters has been instrumental in allowing the Australian public to see and appreciate and ultimately to protect their rare and precious marine legacy and to demonstrate why animals such as the grey nurse shark and the Australian sea lion need be legally and morally protected against imminent extinction.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Ron Taylor worked on both Hollywood feature films, such as The Year of Living Dangerously, Honeymoon in Las Vegas, Return to the Blue Lagoon and the Island of Dr Moreau while continuing to make conservation-conscious, educational awareness focused wildlife features such as In the Realm of the Shark, Shadow Over the Reef and Shark Pod. At the same time, Ron and Valerie themselves became the focus of documentaries made about their lives in the sea, their contributions to scuba diving, exploration and conservation in the features The Sea Lovers and In The Shadow of the Shark.

In 2000, the Taylors were inducted into the International Divers Hall of Fame ceremony held in Grand Cayman. The Taylors have jointly been awarded with the Australian Geographic Society Lifetime of Conservation Award and the Australian Cinematographers Society Hall of Fame, among their numerous honors. The years 2000 – 2011 were filled with dozens of scuba diving expeditions where Ron filmed some of the rarest and most dramatic creatures of the sea: Sperm Whales off the Azores Islands of the North Atlantic, Blue Whales off Indonesia; Great Hammerhead Sharks and Tiger Sharks in the Bahamas; the myriad of strange and often unidentified creatures of the shallow reef and sand slopes of Indonesia, among others.

Ron is survived by his loving wife and collaborator of over fifty years, Valerie.

His legacy is an awareness and appreciation of the ocean and its inhabitants unknown in Australia and throughout the rest of the civilized world fifty years ago. His story, of the journey from an unsurpassed marine hunter to a passionate conservationist putting himself on the line has led the way to a renaissance in thinking and understanding for three generations to the current state of conservation awareness in Australia so admired around the world. Ron Taylor has inspired every major underwater image maker and cinematographer working today and will be admired not only for his flawless technical ability as a filmmaker, but for the quiet, unassuming, grace of a gentle man working with subtle dedication to make the underwater world a better place and a lasting environment for the next generation and generations to follow. There has never been a better friend or dive buddy, a more patient listener or down to earth conveyer of underwater exploration.